The Enchanted

Rock

The Enchanted

RockMichele is the author of several other books

on photography, including a guide to photo trekking, and a technical treatise

on photographic reproduction of documents and artwork. See his home

page and brief list

of books, which are available in the United States through the author.

A woodpile in the first snow of winter. (p.122) |

This book is not a tourist guide, at least not in the traditional sense.

Readers will not find here information on paths, routes or itineraries

of various difficulty.

Nevertheless they will find some suggestions regarding special routes. Throughout the various chapters - and especially through the photographs - they will be invited to perceive the evokativeness of a territory that is among the greatest and wildest of the western Alps, an area which, despite the assault of an inexaustable economical exploitation, is still able to offer scenes of primordial beauty. Credit for this is due certainly to the Grand Paradise National Park, that despite management difficulties and various opposition (overt and covert) has prevented the area from being transformed into a huge leisure park, complete of ski-lifts, roads and luxury multi-story buildings: the sort of things which delight tour operators and local administrators, perhaps the only categories that are still investing energies and hopes in incrementing mass-tourism. The damage suffered by the environment at the foot of Matterhorn, in the range of Mont Blanc and in Val d'Isere (in the very heart of the neighbouring Parc National de la Vanoise) is still unknown in this region. |

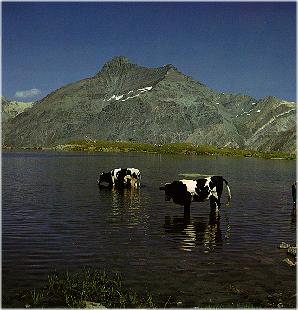

Cows are an essential part of the pastoral atmosphere of the Western Alps. |

Excursionists and skiers looking for real contact with nature, other

than the mere practice of an athletic performance, can really find it here.

Of course, we could debate at length about the timeliness of creating uncontaminated

oases in a world that is galloping towards ecological catastrophy; one

could argue that the existence of parks and natural reserves actually legitimise

the destruction of the environment outside of them.

But until respect for nature becomes part of our way of viewing the

world (until now dominated by a logic of depredation), parks alone are

left to take care of the remaining "wilderness", in order that scholars

and lovers of nature can observe and appreciate what we are relentlessly

destroying in the rest of the world.

|

An old male steinbock with its great horns and characteristic beard. It is dozing. I'm so close to it that I heard it snoring softly. p. 115 "Paradise Lost" |

But if the National Park can protect the environment and preserve it intact for the future generations, it can do nothing to prevent the gradual but unrelenting destruction of the local culture. This degeneration has complex roots: it is a kind of cultural colonization that is difficult to identify and impossible to arrest. Seminars, conferences and debates cannot avoid the fact that every time that an old man dies he takes with him a past made of toil, hardship and daily struggle against an hostile environment (things that nobody wants to preserve) but also a past of knowledge, experience, faith and harmony with nature. The language, beliefs and traditions of the mountains are dissapearing for ever. Neither can the clumsy and superficial attemps made by folk groups bring them back to life: a culture is not a collection of dances, songs and proverbs but a way of understanding the world, an extremely complex semiological code that cannot be recalled approximately by one who is not a living part of it. |

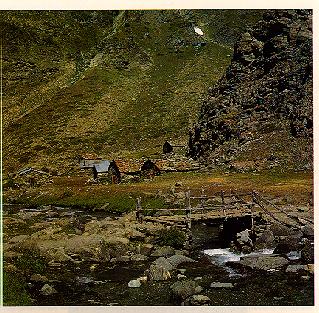

"Baite" (Alpine huts) for summer pasture. Grauson. |

Perhaps this too is an ineluctable phenomenon, part of the world's

evolution. Like many greater and better known past civilizations the mountain

communities and their culture are also going to die out. But without too

much ado about it: in silence, with discretion, as it is the custom here.

This book is by no means a nature guide: readers expecting a precise

and systematic description of plants and animals will almost certainly

be disappointed. But the beauty and magnificence of these valleys and mountains,

their evocation of a yet uncontaminated nature, the emotions stirred by

their wildelife, transcend a purely descriptive dimension and go beyond

an arid scientific exposition. This beauty, these emotions and suggestions

are the core of this book.

|

Not a tourist guide, nor a nature manual about the Park, even less yet another book on mountain photography. This book is simply a "love-song" dedicated by a nature photographer to "his" paradise, that invites to retrace with the author the places he dearly loves. It is an "invitation au voyage" through a personal experience, to discover not so much a territory, but the profound emotions that this land, with its animals and its people, can arouse. Emotions that are evoked by suggestive images and a photographic style that is grandiose in front of glaciers and peaks, tender and almost whispered when portraying the secret life of small animals, felt but not rethorical in describing man's daily labour.

The prose (evocative, poetical but also descriptive and scientific,

and at times vehemently denouncing) leads the reader to the discovery of

forgotten pockets of land, wild valleys, ancient stories that that the

dominant culture has long swept away. Stories of men and mountains, millenary

civilizations and animals. Stories of customs that endure through the centuries

with the sacrality of rites; of docile animals that live in peace and from

the beginning of time obey the eternal laws of nature. And all around,

a world of wild beauty, on the surface hostile and rough, but brimming

with life, where man and the land have lived in harmony for hundreds of

generations: this is the world of the "Enchanted Rock".